History and Development of Democracy from Ancient Greece to the Present

This article is motivated by the funny address of the president of “Wadiya.” This is the kingdom in the famous movie “The dictator”. The article informs on the development of democracy and helps to build future articles.

The Dawning of Democracy in Ancient Greece

A seminal moment in political history occurred when the revolutionary concept of democracy took root in ancient Athens. Many trace the earliest stirrings of democracy to the constitutional reforms of Solon in 594 BCE. To solve festering problems from economic inequality, Solon implemented policies like debt relief and land redistribution that laid the groundwork for the poorer classes to participate in civic life.

Yet the most radical democratic changes were instituted by Cleisthenes in 508 BCE. Seeking to increase citizen involvement in government, he established new governing bodies like the Assembly and Council which gave average citizens direct control over the policies and laws in Athens.

In this nascent democracy, all free native Athenian men, regardless of wealth or class, could have their voice heard by voting in popular assemblies. They could also seek election to public offices that shaped everything from taxation to foreign policy. This direct participation of average citizens in political decisions was remarkably unprecedented for its time.

Of course, Athenian democracy was far from perfect - women, foreigners, and slaves continued to be excluded from any political role. But within the limited scope of enfranchised male citizens, Athens pioneered institutions that allowed direct, hands-on democracy to flourish. The lively Assembly debates that shaped the future of Athens exemplified the freedoms of speech and assembly that remain vital to representative democracies today.

Athens also experimented with one of the earliest forms of selection by lot, using chance and random selection to assign some government posts as a check against electoral politics. The spirit of engaged citizenship and self-governance that defined ancient Athens established a model of participatory democracy that inspired political thinkers for millennia.

The Roman Republic - Democracy for the Few

The Roman Republic adapted elements of Greek democracy within its own unique governmental system. Having witnessed the energetic citizen politics of Greek city-states like Athens, Rome incorporated some participatory democratic structures. Yet Roman culture prized order, tradition, and authority above all.

The Roman Senate gave aristocratic families a powerful role in guiding policy and appetites. But citizens also elected various magistrates and representatives through voting assemblies, creating an early model of representative democracy.

The Roman constitution established a separation of powers between the Senate, assemblies, magistrates, and courts. This system of checks and balances ensured no one faction could consolidate absolute control. Though vastly limited, extending voting rights and civic duties to average male citizens was an innovation for its time.

Yet Rome remained highly elitist and hierarchical, denying any participation to women, slaves, foreigners, or the lower classes. The will of the few privileged male citizens triumphed over any broad notion of rights or equality. Still, the limited participatory elements allowed Rome to claim a form of republican governance mixed with democracy.

This timid adoption of democratic principles within its oligarchic power structure would characterize Rome’s approach to self-rule. The echoes of Rome’s republican institutions would inspire thinkers and revolutionaries throughout the centuries who dreamed of greater liberty. But democracy would not reemerge as a dominant political force until modern times

Enlightenment Philosophers Champion Democracy

The democratic ideals of ancient times were rekindled in the 17th and 18th centuries as Enlightenment philosophers articulated new theories of liberty, equality, and self-governance. Thinkers like John Locke, Baron de Montesquieu, Voltaire, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau offered vigorous defenses of fundamental human rights and democratic participation.

Locke argued in his "Two Treatises of Government" that political authority can only be justified by the consent of the governed. His social contract theory posited that citizens form governments to protect their natural rights to life, liberty, and property. If rulers undermine these rights, the social contract is broken and revolution is justified.

In "The Spirit of the Laws," Montesquieu proposed separating and balancing governmental powers across branches to constrain abuses and protect freedom. Rousseau asserted in "The Social Contract" that sovereignty resides in the collective general will of the people, best expressed through direct democracy.

These political theories fueled calls for broader liberty and democratic self-rule across Europe and its colonies. The divine right of kings was challenged by arguments that political legitimacy could only come from inclusive representation. This intellectual groundwork inspired the American and French revolutions which sought to establish republics governed by the people’s consent.

The spread of democratic thought and action during the Enlightenment era planted the seeds that would eventually topple monarchies and despots. The arguments framing democracy as an innate human right found expression in revolutionary manifestos demanding freedom.

Twin Revolutions Advance Democratic Governance

The democratic philosophies of the Enlightenment sparked revolutionary political action on both sides of the Atlantic in the late 18th century. Inspired by calls for broader representation and liberty, the American colonies revolted against British rule in 1776.

The Declaration of Independence outlined natural rights and the consent of the governed as guiding principles. After winning independence, the new United States Constitution established a democratic republic with authority divided across three branches of government and protected civil liberties.

The French Revolution beginning in 1789 also sought to institute a representative government based on Enlightenment values. Revolutionaries toppled the French monarchy that had resisted reforms. In its place, the First French Republic was proclaimed.

Though short-lived, the First Republic made strides towards direct democracy, extending the franchise beyond aristocrats. Radical changes like emancipation of slaves in French colonies demonstrated the republic’s break from monarchic traditions. However, civil war and political chaos ultimately led to Napoléon’s rise as Emperor, ending France’s first democratic experiment.

Yet the spirit of democracy continued inspiring future generations. Even after the French Republic regressing to autocracy, its revolutionary ideals could not be entirely suppressed. The examples of the American and French Revolutions reverberated worldwide, spurring more movements to challenge entrenched power structures in favor of representative democracy.

Though neither revolution created fully inclusive democracies, their founding documents and innovations provided an aspirational vision of democratic rights and governance. Their republics governed by the people’s consent brought the promise of democracy closer to realization on a larger scale.

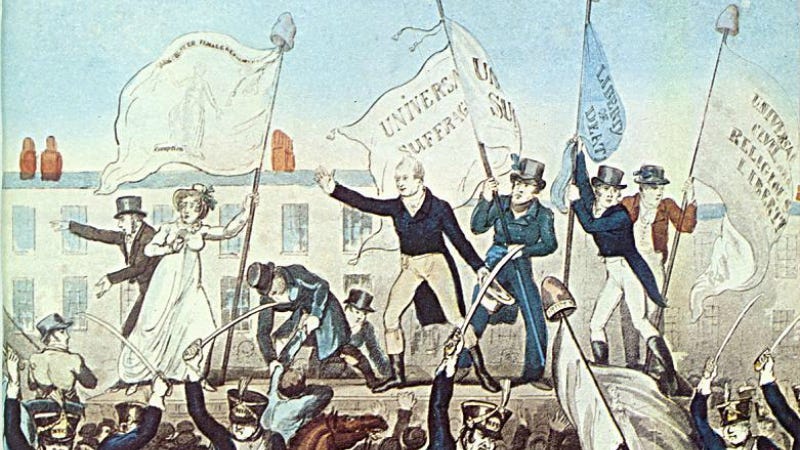

The Steady March Towards Universal Suffrage

The initial democracies of the late 18th century extended political rights only to white male property owners. But the ideals of equality and representation soon fueled organized movements to expand access to voting and participation.

In the 19th century, abolitionists fought to end slavery and extend civil liberties to African Americans. Women's suffrage movements demanded equal voting rights for women. Activists organized petitions, protests, and civil disobedience to achieve these goals.

Reformers argued that democracy was meaningless if large groups remained disenfranchised. Over decades of struggle, voting rights were extended to the working classes, racial minorities, and women in many nations.

For example, in the United States, abolitionists succeeded in banning slavery after the Civil War. The 15th Amendment guaranteed voting rights regardless of race, though discrimination barred most African Americans until the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

After a prolonged fight, the 19th Amendment enfranchised women in the U.S. in 1920. Eliminating property requirements also expanded voting participation among lower economic classes. By protecting marginalized groups’ access to the ballot box, civil rights reformers pushed democracies closer to fulfilling their founding promise of equality.

The broadening circle of democratic participation continued in the 20th century with expansion of voting rights to indigenous peoples, elimination of literacy requirements, and lowering of voting ages. Though progress was uneven, sustained advocacy forced democracies to transform narrow de jure political rights into full de facto access and inclusion.

Democracy Ascendant in the 20th Century

By the early 20th century, the political pendulum had swung decisively towards democracy as the dominant form of governance worldwide. Democratic reforms and self-rule movements succeeded in toppling monarchies and empires across Europe, Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

Institutions like universal adult suffrage, multiparty elections, independent judiciaries, and free press became established features that defined modern democracies. International norms coalesced around principles of human rights, good governance, and fair elections. Organizations including the United Nations promoted democracy globally.

India exemplified the wave of democratic independence movements breaking colonial rule. After Gandhi’s nonviolent campaign for self-governance, India adopted a democratic constitution in 1949 guaranteeing political equality and civil liberties.

Much of Latin America transitioned to democratically elected governments by the 1960s after decades of military dictatorships. Democratic consolidation became linked with economic success and social stability.

However, the spread of democracy was neither linear nor uniform. Authoritarian regimes and military coups impeded democratic progress in some regions. Temporary democracies lapsed into illiberalism or dictatorship, showing the fragility of new institutions.

Ethnic and sectarian conflict challenged unity in diverse societies. Even established democracies faced issues of inequality, discrimination, and corruption at times. The implementation of democratic principles remains an ongoing challenge worldwide. But the overall march towards people power seemed inexorable.

Democracy in Flux: The Struggle Continues

As the 21st century unfolds, democracy globally faces both progress and setbacks. According to Freedom House, around 75% of countries are now categorized as democracies based on criteria of civil liberties and political rights. The majority of states hold competitive multiparty elections with universal adult suffrage as the norm.

Indigenous democratization movements have catalyzed democratic reforms in countries from Tunisia to Taiwan to Chile. landmarks like the Arab Spring show the enduring appeal of democratic ideals. However, some regions like Central Asia and the Middle East remain dominated by authoritarian governments slow to liberalize.

Even established democracies face institutional corrosion from forces like polarized politics, loss of public trust, corporate influence, and xenophobia. Corruption and demagoguery undermine democratic norms in nations from India to the United States. Miscarriages of justice and security threats periodically strain liberties.

Technological and social changes also create new quandaries. Social media enables more voices but also spreads disinformation that polarizes societies. Automation and globalization displace workers and generate inequality that can destabilize democracies. Finding democratic consensus on complex policy issues like climate change proves challenging.

Democratic progress is neither guaranteed nor irreversible. Commitment to values like inclusion, compromise, and equality remains essential. Adapting institutions to empower citizens better and engage marginalized groups is a constant imperative. Though democracies face difficult questions, the participatory spirit of democracy persists as the most just means of realizing human dignity, freedom, and potential.